Pudding Day: A recipe for holiday grief

Pudding Day 2015 at Grandma Doris’ house in Chadstone

My Grandpa Allan always made the Christmas pudding six weeks out from Christmas Day. He made it from a recipe he’d cut out from The Age and stuck into his homemade cookbook. When Grandpa got cancer and became palliative in 2006, my grandma Doris cared for him with complete devotion in a hospital bed set up in the spare room. This was the same small room that had been the childhood bedroom for my mum and her three siblings, in their housing commission in Chadstone.

The small white concrete pre-fab home was guarded by a beautiful row of rose bushes and backed by a yard containing a BBQ Grandpa had built from besser blocks and a garden swing chair where Grandma would retreat when her feet grew weary. The house was covered in family photos, ‘covered’ is an understatement. It was damn well plastered. Nearly every surface and wall was a montage of framed, pinned and even sometimes plastic-wrapped photos of my grandparents, their four children and their eight grandchildren. A living collage of their familial love.

Grandpa died a few months later in his bed, facing an extended family portrait (a snapshot of my teenage goth days) as well as cut out pictures of Australian forests, as Allan had been a dedicated hiker. During the last few weeks of his life, Grandma and their four children cared for him around the clock. As a nightly treat he was given his favourite Stone’s Green Ginger Wine in a sippy cup, though Grandma made sure it was only a single double-shot each night. This was met with amusement by my mum and her sister Janet, who thought that perhaps finally on his deathbed he would be entitled to a little more.

When Grandpa died, the family grieved together, and when Christmas rolled around Grandma decided to make the pudding with her two daughters, Faye and Janet, and her daughter-in-law, Bones. The pudding followed the same, now visibly aged, recipe of Grandpa’s, using his trusty pudding bowl and the sixpences sourced from a jar above the fridge. But this time they added the tradition of each person stirring the bowl to memorialise Grandpa and honour their connection to him, ‘stirring in the love’ is how they put it. Accompanying the pudding, the women drank a single double shot of Stone’s Green Ginger Wine from the ‘good glasses’.

A few years later, tragically my younger brother Jimi died, and then a few years later my mum Faye was diagnosed and died quickly from pancreatic cancer. These deaths shook my grandma to her core. To lose her child and grandchild while she was still alive was unfathomable and cruel. It even challenged her steady Christian faith, symbolically marked by the fact that the day my mum died, she removed her crucifix and never put it back on.The following Christmas my sister and I were welcomed into the tradition in her place. I brought my two-year-old rambunctious daughter Odette, who of course brought spirited, lively energy to the day. We now had two more people to honour and mourn and stir into the pudding, it seemed a dose of tears was always the missing ingredient.

Grandma died in 2016 at the age of 93. She was surrounded by every single member of her large family, packed into a small hospital room, holding her hands and singing to her as she passed away. That year we added a shot of cream sherry to the ritual, the drink she would sip from a small crystal glass at family gatherings.

Since grandma’s death the tradition has continued every year, six weeks before Christmas, now at my aunt Janet’s house in West Gippsland.

I’ve often wondered why this pudding day feels so essential to our family culture, and how much meaning and ritual it holds for us. I think it comes down to a sense of memorialising through food and connection. We stir the pudding for a growing list of people who have died, as a marking of time and the universal experience of loss. We also now stir for people we hold in our hearts to send our love and well wishes, those battling illness, mental unease and pain.

Pudding Day encapsulates for me as a grief worker the theory of continuing bonds: the idea that we never really stop having a relationship with those who have died, it merely changes. This theory was in direct opposition to Freud’s early work where he argued that we needed to sever ties with our dead in order to ‘move on’ and not get stuck in our grief. Perhaps poetically, when Freud lost his own daughter Sophie, he realised this was an untenable pursuit. He learned and then theorised that a healthy mourning process involves transforming, not severing, the bond with our dead. I know intrinsically that we can never stop loving and grieving those we have lost, but we can always make room for them at our table.

So this holiday period I’m sending my love and strength to all who are grieving. I would love to hear about any traditions, cultural practices or perhaps a ritual you wish to begin for those you have died. Feel free to share them with me directly, I’ll hold them gently.

In life and death,

Joh Nyx

joh@nyxfunerals.com.au

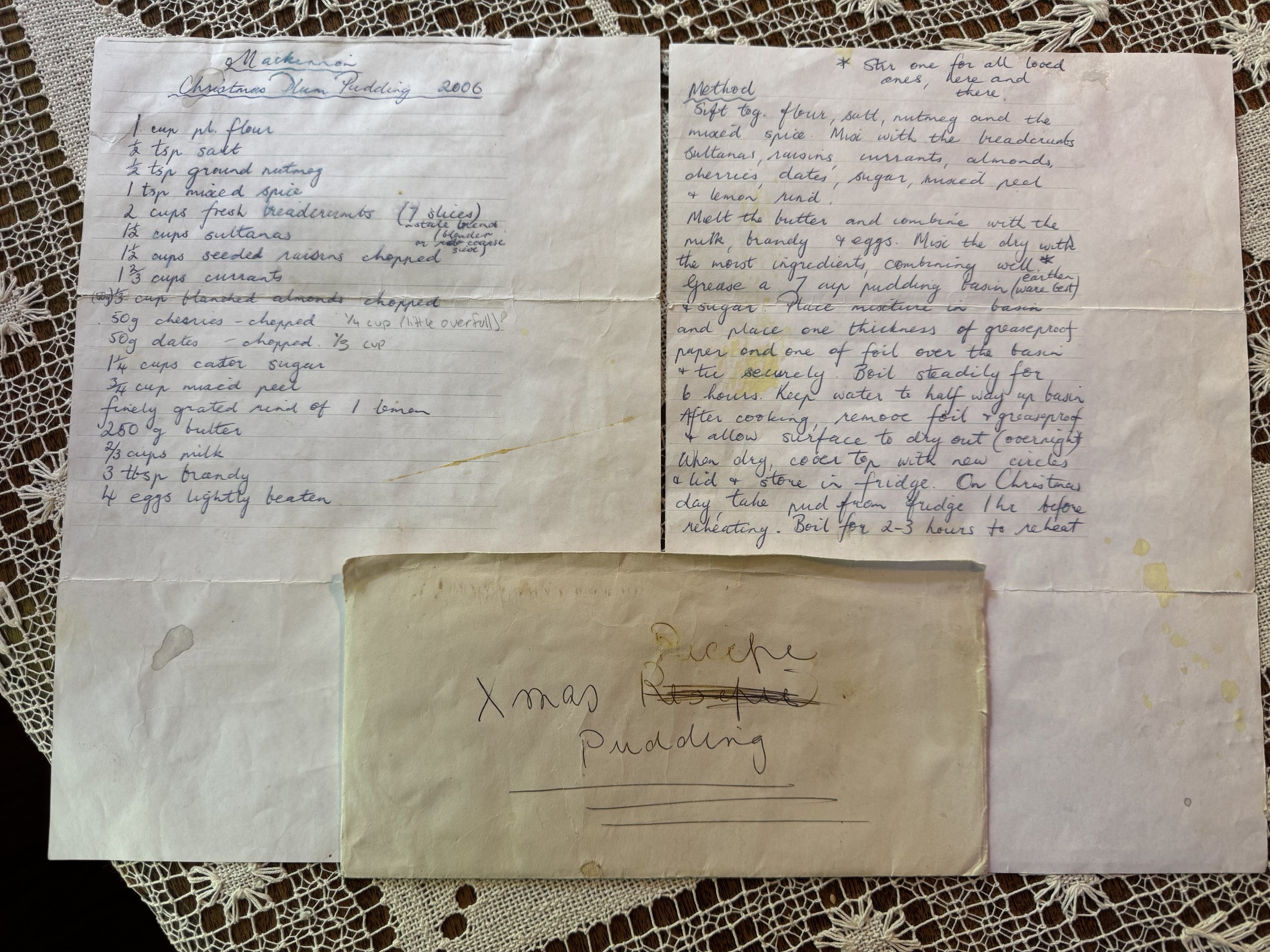

P.S. In case anyone wants Allan’s recipe for Pudding Day here is a photo, meticulously written out by my aunty Bones, as grandpa’s copy had gotten too well loved.